Your Facial Bone Structure Has a Big Influence on How People See You

New research shows that although we perceive character traits like trustworthiness based on a person’s facial expressions, our perceptions of abilities like strength are influenced by facial structure

By Jessica Schmerler on June 18, 2015

Selfies, headshots, mug shots — photos of oneself convey more these days than snapshots ever did back in the Kodak era. Most digitally minded people continually post and update pictures of themselves at professional, social media and dating sites such as LinkedIn, Facebook, Match.com and Tinder. For better or worse, viewers then tend to make snap judgments about someone’s personality or character from a single shot. As such, it can be a stressful task to select the photo that conveys the best impression of ourselves. For those of us seeking to appear friendly and trustworthy to others, a new study underscores an old, chipper piece of advice: Put on a happy face.

A newly published series of experiments by cognitive neuroscientists at New York University is reinforcing the relevance of facial expressions to perceptions of characteristics such as trustworthiness and friendliness. More importantly, the research also revealed the unexpected finding that perceptions of abilities such as physical strength are not dependent on facial expressions but rather on facial bone structure.

The team’s first experiment featured photographs of 10 different people presenting five different facial expressions each. Study subjects rated how friendly, trustworthy or strong the person in each photo appeared. A separate group of subjects scored each face on an emotional scale from “very angry” to “very happy.” And three experts not involved in either of the previous two ratings to avoid confounding results calculated the facial width-to-height ratio for each face. An analysis revealed that participants generally ranked people with a happy expression as friendly and trustworthy but not those with angry expressions. Surprisingly, participants did not rank faces as indicative of physical strength based on facial expression but graded faces that were very broad as that of a strong individual.

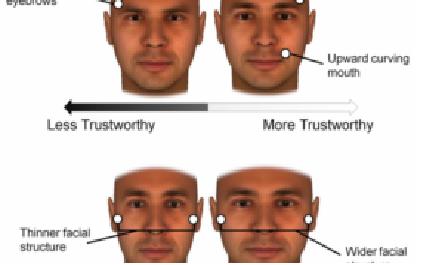

In a second survey facial expression and facial structure were manipulated in computer-generated faces. Participants rated each face for the same traits as in the first survey, with the addition of a rating for warmth. Again, people thought a happy expression, but not an angry one, indicated friendliness, trustworthiness — and in this case, warmth. The researchers then showed two additional sets of participants the same faces, this time either with areas relevant to facial expressions obscured or the width cropped. In the first variation, for faces lacking emotional cues, people could no longer perceive personality traits but could still perceive strength based on width. Similarly, for those faces lacking structural cues, people could no longer perceive strength but could still perceive personality traits based on facial expressions.

In a third iteration of the survey participants had to pick four faces out of a lineup of eight faces varied for expression and width that they might select either as their financial advisor or as the winner of a power-lifting competition. As might be expected, participants picked faces with happier expressions as financial advisors and selected broader faces as belonging to power-lifting champs.

In a final survey the researchers generated more than 100 variations of one individual “base face” by varying facial features. Participants saw two faces at a time, and then picked one as either trustworthy or high in ability or as a good financial advisor or power-lifting winner. Using these results, a computer then created an average face for each of these four categories, which were shown to a separate set of participants who had to pick which face appeared either more trustworthy or stronger. Most of the participants found the computer-generated averages to be good representations of trustworthiness or strength — and generally saw the average “financial advisor” face as more trustworthy and the “power-lifter” face as stronger. The findings from all four surveys were published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin on June 18.

Taken together the findings suggest facial expressions strongly influence perception of traits such as trustworthiness, friendliness or warmth, but not ability (strength, in these experiments). Conversely, facial structure influences the perception of physical ability but not intentions (such as friendliness and trustworthiness, in this instance). In addition, decisions that involve guessing at the possible intentions of a person such as to whom you would entrust your money management are more strongly influenced by facial expression, whereas those based on physical ability such as whom you would bet on in a sporting event are more strongly influenced by facial structure.

Previous studies also have shown the effect of facial cues on how we perceive and interact with others but this new work reveals how perceptions of the same person can vary greatly depending on that person’s facial expression in any given moment. This variability “has implications for both the people presenting themselves and the perceivers in social interactions,” says Jonathan Freeman, a social neuroscientist at New York University and senior author of the study. So, we might consider the impact of our facial expressions in the photos we post online. At the same time, in an ideal world people who look at our photos would give us the benefit of the doubt and hesitate to make spontaneous judgments based only on a single image.

The findings above come with a big caveat: Only male faces were shown to subjects. The researchers chose this approach because previous studies involving the ratio of facial width to height have shown that greater facial width is often associated with higher testosterone levels as well asheightened aggression and strength in men. Studies of facial width and height in females have shown mixed results, so presenting study subjects with a mix of male and female faces would have yielded inconclusive results. Despite the relative lack of evidence on how facial structure influences perception of women’s faces, there have been humorous portrayals of popular speculations. Future research, however, is needed to definitively establish whether any such patterns exist.

Furthermore, the researchers refer to “ability” when discussing physical strength in the study. No specific measurements were made, for example, of perceptions of intellectual ability or ability to perform in certain job positions. These abilities are more abstract and thus might rely on a combination of different dynamic and static facial cues, Freeman explains, so it would be difficult to test these relationships definitively.

In our everyday lives this study and others make clear that although we might try to influence others’ perceptions of us with photos showing us donning sharp attire or displaying a self-assured attitude, the most important determinant of others’ perception of and consequent behaviortoward us is our faces.

So the next time you want to win someone’s trust, try a smile and a happy face. But for those folks hoping to get picked for a pick-up game of football, basketball and so on, don’t worry about your facial expression. The best you can do is hope you have a wider face and then let your physical prowess speak for itself.

0 Comments